Pollinator Habitats and Facts

Why are Pollinators in Trouble?

The introduction of non-native invasive plant and animal species, habitat loss, disease, climate change, pesticides and modern crop practices producing large areas of land lacking plant diversity and good forage sources have all contributed to native pollinator and honeybee loss.

Pesticides

Neonicotinoid pesticides (Neonics) are systemic, meaning the plant transports them throughout itself and has them present in tissues, pollen and nectar.

The Canadian federal Pest Management Regulatory Agency concluded that the majority of honey bee mortalities in Ontario in 2012 and 2013 were a result of exposure to neonicotinoid insecticides. This is likely due to contaminated dust exposure generated during the planting of neonicotinoid-treated corn and soybean seed. Treated seed dust lands on the pollinators themselves or on surrounding vegetation and if not absorbed when cleaning themselves, the bees carry the pesticide back to the hive.

Honeybees form large colonies and honeybee behaviour encourages worker bees to gather from productive nectar source areas that may have been treated or contaminated by neonicotinoids. Once a worker bee locates a good nectar source, it flies back to the colony and communicates the location to other worker bees using the “bee dance.” The other bees then fly off to utilize this food source. This means whole colonies may be weakened or die due to exposure from a single source.

Effects on European Honeybees

– Death due to direct exposure

– Impacts to hive health through chronic exposure affecting pollen gathering, navigation and reproduction.

– Neonicotinoid residues brought back to hives are linked to Colony Collapse Disorder (CCD) and other diseases.

Native Bees and Pesticides

Pesticides seem to affect the reproduction of, or the offspring of the generation exposed to the pesticide. Fungicides are also suspected of affecting native bee larval survival, perhaps affecting their digestion or nest recognition. Toxic effects hundreds of times more potent to both native bees and European honeybees are observed when both pesticide and fungicides are present as when used individually (Maryann Frazier, entomologist at Pennsylvania State University).

A study of pesticides and their effect on native orchard pollinators by Cornell University, published in June of 2015 in Proceedings of the Royal Society B, found pesticides had less impact on native bee populations if natural areas were nearby.

Currently it is thought that having a significant amount of natural areas around agricultural areas:

– Provides a larger pollinator population, so if pesticides kill some, others can still pollinate.

– Provides refuge from constant pesticide exposure.

– Provides a diversity of available pollinators.

Current Limitations to European Honeybee Pollination Efficacy

“Because production of our most nutritious foods, including many fruits, vegetables and even oils, rely on animal pollination, there is an intimate tie between pollinator and human well-being,” Mia Park, Ph.D., assistant professor at the University of North Dakota.

Colony Collapse Disorder or CCD, is having a huge impact on agriculture. American agriculture has relied on European honeybees for centuries. Honeybee hive managers are currently experiencing losses of 30-40% each year, with 70% losses occurring during the worst “colony collapse” years. Farmers dependant on rental hives face high costs or production decreases due to limited honeybee availability.

Crop pollination however, is possible without relying on honeybees.

Cornell University Researcher Mia Park demonstrated that some native bees, like the ground nesting Andrena species, crawl deep into flowers and are four times more effective pollinators than European honeybees. Based on this knowledge, researchers used only native pollinators to pollinate their orchards and were amazed at the results.

Advantages of Native Pollinator Species

Many crops are pollinated more effectively by native species than by honeybees. According to Cornell University entomology professor Bryan Danforth, native pollinators are significantly better pollinators being two to three times more effective, and until colony collapse disorder created a crisis, the role of native bees in crop pollination has been unappreciated. With the right habitat requirements, native pollinators are more available and plentiful than honeybees, and the large variety of species are much less affected by the colony collapse disorder that has caused a large decline in honeybee numbers. Native bees are also pollen collectors, and transfer pollen more efficiently between plants than do their honeybee cousins who are more interested in nectar collection.

Introducing native plants to field edges or nesting/forage sites within fields attracts these native pollinators, while enhancing crop pest management by attracting native predatory insects as well. Since native pollinator species will only fly 200 yards to one mile to acquire pollen and nectar, large open fields would require strategically located nesting sites and forage plants. These sites could be located along drainage ditches, woodlot or forest edge, and other areas of marginal to low productivity.

Native plants attract many predatory insects like wasps, ants, true bugs and beetles that are of great advantage in biological control of crop damaging insects. These predators are attracted both to the nectar and pollen food source as well as to the insects they prey on. They perform damage control while helping pollinate as well.

Having a diversity of native flowering plants suited to the soil type that flower sequentially from early spring to late fall will provide forage for pollinators. These plants can be introduced to marginal or fringe areas of low return like existing fence-lines, grassed waterways, ditches or streams to attract native pollinators.

Native plantings can further reduce phosphorus loading, improve soil conservation, water retention, and the environmental and aesthetic value of the land they are on. Planting native plants like the one’s listed here suited to the area’s soil types and growing conditions, will help native pollinators to access important food sources and they in turn will help pollinate our crops. Plantings are best done by choosing the plants best suited to the area in which they will be planted, then planting in clumps interspersed by clumps of other suitable species. When choosing native species, be aware of when they are flowering, since you want to offer the pollinator’s a food source for as much of the growing season as possible. Many native bee species have queens that overwinter, and need a food source that is available in the fall so they can survive.

You can help by planting a native garden. The charts in the following link outline native plants that attract native pollinators and beneficial predators for the growth conditions and soils present in most of Southern Ontario. Honeybees are the only species not native to Ontario on this list, but are included since they also contribute to crop pollination.

Our Native Pollinators – Longwoods Road Conservation Area Native Plant Garden Kiosk Display

The Masons and Leafcutters are a two of more than 400 types of bee native to Ontario with relatives all over North America. Native bees are extremely important to native plants, pollinating them to make seeds. This maintains the biodiversity of all the living organisms that depend on these plants, including us. The amazing thing about our native bees is that they are very effective pollinators of many plants, including the crops we depend on for food. Science has only recently discovered the value of native bees, finding they can be two to three (sometimes up to four times) more effective at pollinating certain crops than the non-native Honeybee, which originated in Europe. Native bees are undergoing the same challenges to their survival as many other creatures, mainly due to loss of habitat from human activities and land use/development. Their numbers have taken a severe hit with the use of neonicotinoid pesticides, which do not discriminate between killing pests and crop helpers. Agricultural land use practices have also reduced native pollinator numbers since wind barriers and buffer strips that once provided pollen, nectar and nesting opportunities for bees and other pollinators have been removed so large equipment can plant every last millimeter of soil.

By using best management practices and planting buffer strips especially around fields bordering streams and other water sources, we can provide much needed habitat resources for these important pollinators, prevent our soils from washing away, prevent surface runoff of fertilizers that cause algal blooms in our Great Lakes, provide habitat for native biologic pest control agents, and get free pollination of our crops! If you live in the town or city, a native plant garden encourages these entertaining additions and goes a long way to help native birds and other wildlife as well.

A Diversity of Pollinators

1. Osmia species or Mason Bee – Range: 30 species of Osmia exist east of the Mississippi River. Native to North America this genus includes some of the most economically important bees to agriculture. Many of these bees pollinate orchards and commercial crops more efficiently and cost-effectively than honeybees. Pollination of an orchard of apples, plums, cherries or almonds needs only 300 Osmia lignaria. The same job would require 90,000 European honey bees. Some Osmia species build nests entirely of mud, earning the name of Mason Bees. Their head-to-tail size can range from 2.5 to 12.7 mm (1/10th to ½ an inch). For more on Mason Bees, please look at the Mason Bee section below.

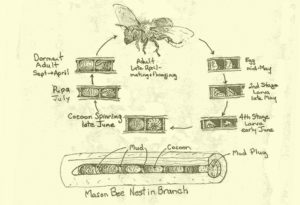

Mason Bees belonging to the genus Osmia overwinter as adults in their nesting chambers. When April arrives and spring melt occurs, the males emerge first and find areas where females are emerging. Mating then takes place and females can lay their eggs after a two day development in their body. Being solitary nesters, Osmia females each make their own nest, using holes in twigs, reeds, branches, and tree trunks left by beetles and other wood-boring insects. They will nest close to other female’s nests forming what looks like a huge colony. Once a nest-site is located the female will zoom back and forth in a zig zag pattern to remember the exact location of her nest. Females have an individual scent which they use to mark their nests, allowing them a means to find their own brood in large congregations of nests.

Mud is used to form a back wall near the innermost end of the nesting chamber. Mud from clay soil is preferred to make the “masonry” walls as this forms a solid concrete which predators can’t penetrate. The large mandibles (jaws) of the female are used to dig and carry the mud along with their front legs. If surface mud is unavailable, these bees will tunnel down into the soil until they can acquire suitably wet and sticky clay.

The pollination ability of these bees is enormous due to the way they collect nectar and pollen from flowers. Entering a flower, the bees’ body hairs collect pollen from the anthers (male organs) of the flower. The bee also sips nectar and stores it in its “honey stomach”. The female will groom herself, brushing and pushing the pollen backward along her body until it reaches the scopa on her back legs. The scopa are long stiff hairs specialized to hold pollen during flight. When the bee is fully loaded she returns to the nest to mix the nectar and pollen into a nutritious loaf of “bee bread”. It is onto this loaf she will lay a single egg then seal off the chamber with a wall of mud. The process begins again until the nest tunnel is full of chambers. The final chamber closest to the entrance is left empty. This forms a deterrent to potential predators invading the nest. Finally the outside entrance is sealed off with a large plug of mud (Figure 1).

The mother bee starts the nest by late April and the next generation of adults will overwinter in the nest chamber then chew their way through the walls with their strong mandibles to emerge the next April when the snow melts. Male bee eggs are laid last, take less time to develop and emerge from the nest first, followed by the females. The mating and nesting cycle then begins again (Figure 1).

2. Nomada Bee or Cuckoo Bee species – Range: across North America. These native bees’ common name of Cuckoo Bees describes them well. Like the Cuckoo Bird they lay their eggs beside other bee’s (the host bee’s) eggs. The Cuckoo Bee larvae hatch and kill the host bee’s young then eat the pollen ball the host bee had made for its young. They then develop to adulthood in the host bee’s nest chamber. Around forty species of Nomada occur in Canada, and Andrena bee species are most often their targets. Andrena bees tunnel into the ground to lay their eggs, and the Nomada bees can be seen flying from one Andrena nest to another, checking to see if the way is clear to go in and lay an egg. The scientists who named them noticed the way they never stopped moving from place to place, that’s how they got their Nomada genus name. One weird thing about Nomada bees is that the males have a smell like that of female Andrena bees. No one has yet figured out why this is.

Cuckoo bee in the genus Nomada

3. Flower, Hover or Syrphid Fly – Range: Many types of hover flies occur in Ontario.The larvae of syrphids look like small caterpillars and eat a large variety of things. These larvae eat aphids, scale insects, mealybugs, corn borers and other soft-bodies insects. Other syrphid fly larvae are known as rat-tailed maggots and occur in stagnant aquatic environments where they feed on decaying organic matter. Adult flies act to pollinate flowers, feeding on the pollen and nectar. They look similar to bees but have only 2 wings, where bees have 4. This bee mimicry can be a benefit when predators are around, or a drawback if flyswatters are nearby. Flies like these act to pollinate over 48 of the 115 leading global crop species.

4. Monarch Butterfly – Danaus plexippus – Range: Feb. to March Adults of Generation 4 emerge from hibernation in Mexico and fly to northeastern U.S.A and southeastern Canada where they mate and lay eggs. Eggs hatch March-April to become Generation 1, whose caterpillars feed and form a chrysalis and become adults for 2-6 weeks. Generation 1 remains close to where it was born and doesn’t migrate, but lay eggs which become Generation 2. These eggs will hatch May-June, and become adults which do not migrate but lay the eggs for Generation 3. Generation 3 is born July-August and lays eggs that become Generation 4. Now things change. Once Generation 4 become adults they migrate south to Mexico, and will live not 2-6 weeks but up to 8 months and continue the cycle. The monarch caterpillar feeds on milkweed species and acquires cardenolides in its tissues, giving a toxic protection from predators. The adult butterfly pollinates the milkweed plants in return, forming a symbiotic relationship.

5. Great Spangled Fritillary Butterfly- Speyeria cybele – Range: Alberta east to Nova Scotia, south to central California, New Mexico, central Arkansas, and northern Georgia. This is one of our most common fritillary or “brush-footed” butterflies. Males patrol open areas for females. They recognize each other by their bright ultraviolet spots on the underside of their wings. A pheromone perfume is released when they approach each other that gets them in the mood. Eggs are laid in late summer on or near host violets. Newly-hatched caterpillars do not feed, but overwinter until spring, when they eat young violet leaves. The young only come out during the night to feed.

6. Woods Firefly – Photuris pennsylvanica – OK, these guys aren’t really flies, nor are they bugs, even though another common name for them is lightning bugs. They are really a type of beetle, so they really should be called Lightning Beetles. No matter which name you choose to call them by, they are remarkable in how they act and help native plants.

There are fireflies of many types. The larvae of the firefly, called “glow worms,” live in leaf litter and soil and are voracious predators. They eat other insects, mites, earthworms, slugs and snails. The larval stage can last for years before the larvae pupate and emerge in spring as adults. The adult fireflies of some species do not eat, while some consume flower nectar or pollen, helping fertilize other plants. The Woods Firefly belongs to a group or genus called Photuris that has many predators in it.

Photuris females will lure in males of other species by mimicking their blinking patterns, so the hapless males fly over to the females in hopes of finding love, but are consumed instead. This behavior has earned these particular lightning beetles the nickname “femme fatale fireflies.”

Lightning beetles produce their own cold light through a chemical process called bioluminescence. The light shines from their tail area, and is stimulated by brain signals to release an enzyme called luciferase. When this enzyme combines with the chemical compound luciferin, it activates it in the presence of oxygen and energy (ATP) and light is produced. This bioluminescence process is up to 99% efficient and generates no waste energy in the form of heat. This ability was developed to find mates during dark nights, but as you can see, sometimes it’s wise to stay away from the light!

Lightning beetle gene markers have been used in cancer research to track metastasizing cancer cells.

Take-Away Message – Numbers of lightning beetles are declining due to habitat loss of the wet woodlands and marshy areas they need to survive. Monarch numbers are at record lows and the species could become extinct within our lifetimes. Native bees are declining due to agricultural practices of pesticide use and the plowing under of shelter belts and buffer strips which once encouraged native plant growth while reducing surface runoff of applied fertilizers. Recognizing everything these small organisms do for us, should we not act as environmental stewards to help them? Like the First Nations that lived alongside them for thousands of years, we need to give something back in return.

You can help by planting a native garden. The charts in the following link outline native plants that attract native pollinators and beneficial predators for the growth conditions and soils present in most of Southern Ontario. Honeybees are the only species not native to Ontario on this list, but are included since they also contribute to crop pollination.

Our Native Bees Display Panel

The following picture contains the numbered silhouettes of the different bees displayed in the kiosk panel. Match the number to the bee you’re interested in then scroll down to find out more about it in the text below.

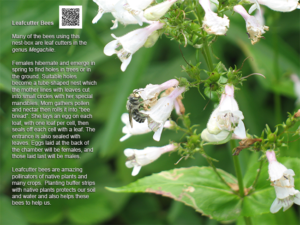

1. Megachile sp. – Leafcutter Bee – Their scientific name alludes to their large jaws which these bees use to cut leaves into small pieces which are then taken to line their nest tunnels. Over two dozen species of Megachile occur in Canada. Some species of Megachile specialize in fertilizing sunflowers (Helianthus) and one species is only focused on the pollen and nectar of the Evening Primrose (Oenothera biennis). For some crops such as alfalfa, Megachile bees are three times more efficient at pollinating than are honeybees.

Nesting in holes in trees, females use their own individual holes/tunnels. Females can tell which hole is theirs since whenever she arrives, the female drags her abdomen at the entrance and leaves a secretion which has her own particular scent. Males will often swarm around the nest entrances and wait for the females to arrive to mate with them. Females cut and carry sections of leaf to the nest tunnel and form them into a cup-shaped capsule into which they place a ball of pollen and nectar called “bee bread.” She then seals of the end and begins another nesting capsule. It may take her an hour and a half to 3 hours to form one nest capsule.

These bees have large, strong jaws or mandibles which they use to cut .635 to 1.27 cm (.25 to .5 inch) circular pieces from leaves. The bees carry these leaf circles into their nest chambers, which can be holes in the ground or old beetle tunnels in trees, where they then place them to form a wallpaper along the sides of the tunnel. Once the wallpaper hanging is done, the bees gather pollen and nectar from many plants and make a loaf of “bee bread” from this. Onto this loaf the female lays an egg, then seals off the end of the leaf nest cell. The loaf provides food for the developing larva. Female eggs are laid first toward the back of the chamber. The females take longer to develop, while the males take a shorter time so their eggs are laid closer to the entrance of the nest chamber. All of the nest-making and egg laying occurs in the time between March and mid-June, meaning these bees are very important pollinators for early blooming spring plants. The Leafcutter Bee nests are very similar to those made by the Mason Bees in Figure 1. above, but leaf material is used instead of mud.

Leafcutting bees are important pollinators of many wildflowers. They also pollinate fruits and vegetables and are used by commercial growers to pollinate blueberries, onions, carrots and alfalfa.

2. Heriades sp. – Four species of these small black bees occur in southern Canada. Their scientific name refers to the wooly patches of hair found on their abdomens. These bees commonly nest in holes left by beetles in trees and some nest in pine cones. They use resin to seal off the individual cells of their nests. Heriades are generalist pollinators, meaning they visit a huge variety of plants for pollen and nectar helping to fertilize all of them. Their small size lets them access pollen in small flowers and tight spaces.

3. Augochlorella aurata – Green Sweat Bee – In spring, the female emerges from hibernation and digs a tunnel into the ground, she then digs out a chamber into which she places a cluster of nest cells. She places pollen and nectar and lays an egg into each cell. The female young hatch and take over pollen and nectar gathering duties while the original female stays in the nest laying eggs. This “queen” lays three generations per year with the last generation emerging in September. The females from this last generation will form the “queens” of the coming year.

These bees pollinate many plants and will land on your open skin in summer to lap up a bit of your sweat which provides them with moisture, salt and a bit of protein to help them in their journeys.

4. Osmia sp. Bee – Range: 30 species of Osmia exist east of the Mississippi River. Native to North America this genus includes some of the most economically important bees to agriculture. Many of these bees pollinate orchards and commercial crops more efficiently and cost-effectively than honeybees. Pollination of an orchard of apples, plums, cherries or almonds needs only 300 Osmia lignaria. The same job would require 90,000 European honey bees. Some Osmia species build nests entirely of mud, earning the name of Mason Bees. Their head-to-tail size can range from 2.5 to 12.7 mm (1/10th to ½ an inch).

5. Halictus sp. – Sweat Bee – Halictus bees consist of an amazing variety of lifestyles. Some are eusocial and like honeybees form colonies, while some are solitary and nest alone. They are generalists and pollinate a wide variety of plants. Scientists believe Halictus species are key pollinators of carrots, onions and sunflowers. Unlike honeybees, female Halictus are all born fertile and if a “queen” dies, one of her daughters or sisters can become queen and continue laying eggs for the colony. Worker bees can also leave the colony and set up their own colonies.

Halictusspecies are ground nesters and can form single nests or large colonies underground. The surrounding environment seems to determine whether some species of these bees become social or solitary. If a large amount of flowers and warm temperatures are present, the young larval bees get large amounts of nutritious “bee bread” and become large and are able to go off to form their own nests. If flowers are not plentiful and temperatures are cool, the founding “queen” can only form small loaves of bee bread, and her offspring grow to be smaller than herself. The queen can then dominate them and they stay to gather pollen and nectar to feed the queen’s subsequent offspring.

6. Lasioglossum sp. – Sweat Bees with hairy tongues – These small bees belong to the largest, most numerous bee family in North America and the world. Some species of these bees are solitary but many are eusocial and form colonies with queens and worker bees. Most Lasioglossum nest in the ground, but a few will use rotten logs. Like other sweat bees they will land on you and drink your sweat. Take advantage of this by letting them tickle you and watch as their tongues extend to get every drop.

7. Anthophora sp. – Digger Bees – Walking along flat, sandy areas or roadsides in spring may allow you to see what look like a city of anthills on the ground. Look closer and you may see these are not occupied by ants but by fuzzy heads peering out at you. Anthophora bee females dig a nest in the ground by placing their large mandibles into the soil then spinning very quickly round and round. They make individual nests but will nest close to others of their kind forming what looks like a colony. These bees emerge early in spring and are important pollinators of early flowering plants. They will shiver to warm themselves then will maintain that warmth as they fly gathering pollen and nectar. Possessing a significant amount of fine abdominal hair, these bees are very effective pollinators. They are known as “buzz pollinators” since they don’t need to land, they just brush their pollen laden hairs onto the plant’s female receptive organs as they fly past. Scientists have found that in California, tomato harvests are much greater when these bees are present compared to having honeybees present to pollinate the crop. Canada has 11 species of this bee. To keep their underground nests dry during spring freezes, snowfalls, thaws and rains, these bees secrete a waterproof coating which allows their nest chambers to drain with no damage to the structure or their eggs or larvae.

Resources

Click on this brochure for more information!